With our ready access to the information superhighway and more efficient access to the world’s ears at our fingertips, getting the right information out there shouldn’t feel so challenging. But communication, online particularly, is fraught with complexities.

Current trends emphasise the sharing of short form, quick fire, snazzy bites, simplified for rapid assimilation until we scroll on until the next bite.

Indeed it has been, in some quarters, considered helpful to provide short form education to trainers and emphasise the simplicity of reward-based training to recruit more to “our side”. And that’s certainly coming back to bite us in the a**.

Dumbing down behaviour information doesn’t sit well with me. I will admit I am not a fan of the proliferation of shorts and reels, particularly those consisting of to-camera talking. They make me scroll on and fast.

But the use of shaming and blaming to facilitate behaviour change, particularly directed at guardians, is inexcusable.

The internet makes shaming easier, more efficient and impactful, fueled by anonymity and by rousing community support. One online community decides what’s acceptable and another opposes…and round and round we go. These attacks may suit the orgnaisation or government institution that originated the tension.

Blame culture

Attempting to shame and guilt people into behaviour change may not be effective, particularly where they may already experience negative emotions. Indeed, further shaming and guilting can lead to the exact opposite outcomes to those intended. (Agrawal & Duhachek 2010)

Indeed shamers often don’t believe their behaviour contributes to blame and shame (Muir et al, 2023). I truly believe that most are doing so because they want to make a positive difference and care deeply for their cause.

When it comes to canine welfare, and the well-being of their people, there are copious examples of the failure of our messaging and the reliance on shaming and blaming. But this piece is already almost 2500 words so I’ve just discussed two…

The Brachycephalic Dog Paradox

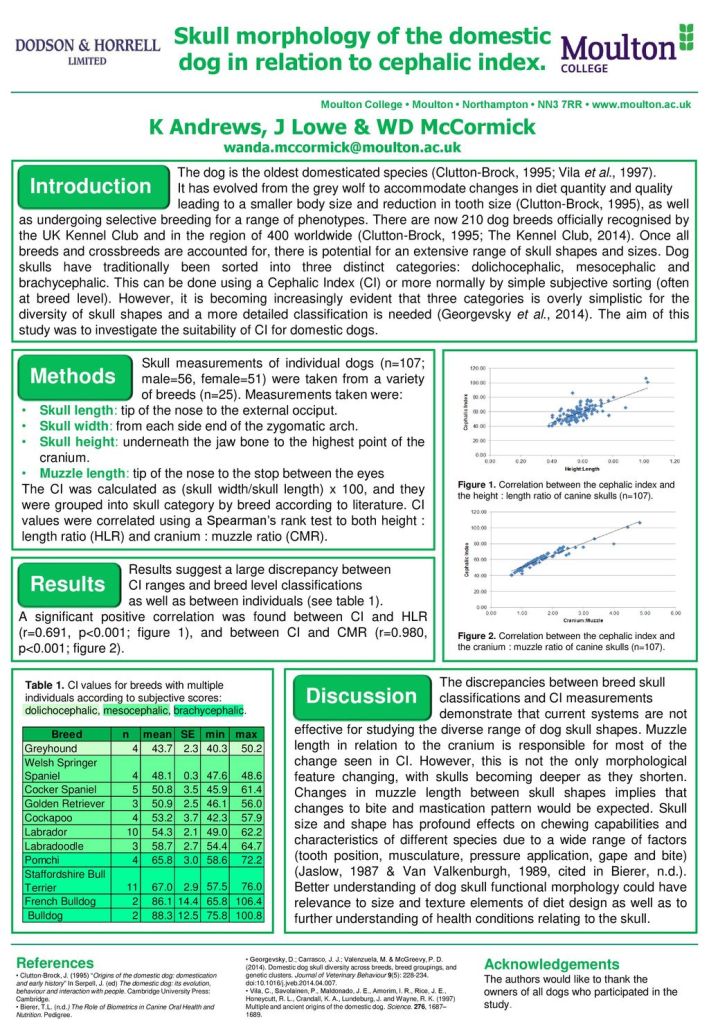

Classifying dogs as brachycephalic refers to head shape and proportions. Round faces, high foreheads and forward-facing, round eyes likely appeal to humans due to our care-seeking tendencies directed toward “cute” and infant-like features (Lorenz 1943)

And as humans we have selected for these features, in our dogs (and other animal companions), that satisfy this ‘cute-effect’. (Paul, et al, 2023)

Extreme Communications

While some degree of brachycephaly may have been functional for breeds of dogs doing some historic jobs, exaggerating these features is associated with a range of diseases, disorders and welfare challenges. (e.g., O’Neill, et al, 2015 & Packer, et al, 2015 & O’Neill, et al, 2019)

These dogs have been labelled as “extreme” brachycephalic dogs, usually directed toward the most popular, French Bulldogs, Pugs and English Bulldogs. While BOAS testing for breeding dogs is being rolled out in Ireland (e.g., here), it’s difficult to find what exactly defines “extreme”. There appears to be circular explanations for the term’s use, one paper applying it because another paper did (e.g., Ekenstedt et al, 2020, & explanation of its use here)

This is an inflammatory word, and perhaps, that’s the intention of its use. We have a cephalic index (e.g., illustration in Bognar, et al, 2021) but this system may be inadequate in encompassing the features that contribute to health and welfare concerns and describe the variations across domestic dogs (see below).

Inflammatory language is designed to convey a particular and strong position through the generation of ’emotional’ responses.

These same texts exclaim disbelief that, despite well publicised health issues associated with “extreme” bracephaly, the labelled breeds become more and more popular. (Paul, et al, 2023) (Packer et al, 2019)

This “paradox” has been further explored by Packer, et al, 2019, revealing “extremely strong” relationships between brachycephalic dogs and their humans.

Cognitive dissonance processes are concluded to be behind believing that one’s own dog’s health is fine versus the health of others of the breed.

Difficulty breathing and other conformational problems have become normalised and as breed traits, sometimes, even considered “cute”. (Rohdin, et al, 2018) (Packer, et al, 2012)

For example, I regularly see videos and photos of bulldogs resting with their heads propped up, with their tongues out or sleeping while holding a toy in their mouths. (Niinikoski, et al, 2023) For sure this might create an adorable picture but on the flip side is likely due to difficulties with breathing when resting. Not so adorable at all.

Might these perceptual errors increase and intensify the emotional attachment felt toward one’s own dog?

What’s the best way to approach cognitive dissonance and distortions?

What’s the best way to appeal to the love and relationships people have for their dogs?

I don’t think we have these answers yet, but this is worth consideration before we shame and blame.

Selecting for many conformational features, and deformities, in dogs leads to compromises to their welfare. (Packer & Tivers, 2015)

Closed gene pools (and unwillingness to outcross) and selection of popular sires are making breeding our way out of these problems more challenging.

A BOAS assessment compromising largely of a 3-minute activity test certainly makes it seem like “responsible” breeders are doing something, but is that really going to make the widespread and multi-level changes that are required?

I cringe when I see open discussions, usually online and via social media, demonising people’s choices, making accusations and blaming and shaming. Given the continued and growing popularity of these dogs, perhaps our messaging isn’t doing what’s intended. And that means we might need to change our approach…

It’s your fault. Be responsible.

Recently, a long-threatened campaign to promote “responsible dog ownership” was launched in Ireland by Minister for Rural and Community Development, Heather Humphreys TD.

The Department has gone to great lengths to develop working groups on dog control and on companion animal welfare. The former has produced a report outlining their recommendations largely prioritising legal instruments and legislative approaches. While the latter have recommended against the use of brachycephalic dogs in advertisements, banned the importation of cropped dogs unless specific documentation/licensing criteria are met, and most recently, pushed for the banning of ‘shock collars’ but under very specific conditions (not for dogs already using them and only hand-help remote devices). Apparently a database will be established of all those already using these collars and that will somehow be enforced.

This latest campaign aims to remind owners of their legal responsibilities and is built upon a slogan: “If your dog attacks a child, it’s not your dog’s fault. It’s yours.“. The focus, so far, is on increasing fines, investing some money in dog pounds, and the formation of the working group.

What does “responsible dog ownership” mean anyway?

When we are shocked by a dog “attack” that’s reported, when we are disgusted by dog poop that’s not scooped, when we’re annoyed by barking dogs, and when we are shocked by cruelty, we call on “responsible” ownership to fix it all. Just be responsible….right?! If that’s all that’s required, why is it so hard to improve safety and welfare?

With our companion dogs becoming more and more a part of our human worlds, increasing controls and regulations are implemented. Guardians are viewed as having moral obligations and legal requirements in keeping their pets.

‘How to be a responsible dog owner‘ from the same Irish government department responsible for the above campaign and slogan.

But here’s the problem…we don’t have a much of an idea of how to be “responsible owners”.

Are we owners?

Some time ago I made a declaration on social media to make efforts to change the language I used in several different professional contexts. I did this for accountability and to seek others’ insight. One of these declarations reviewed my use of the term “owner”, favouring “guardian” instead.

There are long standing arguments about how we identify in terms of our relationships with our animal companions.

Am I my dog’s owners, as I am my car’s owner? Legally, I am compelled to do various things as evidence of ownership such as holding a dog license and his microchip certificate. In the eyes of the law, I am an owner of this living being as I am the owner of my inanimate car.

He’s certainly my dog, just as I’m sure he views me as his human. But legal ownership doesn’t quite hit the mark in fully representing our relationship. I certainly view our relationship as more than that shared with items of property; for starters, my car is replaceable…my dog is not.

I am his caretaker, responsible for his safety, nurturer of his well-being. And that brings responsibilities extra to the bare minimum required by law.

While waiting for the legalities and societal views to catch up, I’m settling on the term “guardian”, but the implications of this may not be evident just yet.

More than scooping the poop!

Westgarth, et al, 2019, argues that calls for “responsible dog ownership” echoes “civic responsibility”, seeking people to take responsibility for their actions, understand their roles in their communities, and collaborate to promote the welfare of others.

It’s pretty tricky to find discussions of this outside of basic legal requirements of living in society. But humans are somewhat prepared for living in human society by virtue of being humans and being reared within human cultural rituals. Dogs are not…unless their humans make specific efforts to guide them. And therein lies a problem.

Responsibility evolves

As our relationships with our animal companions evolve, integration of some of these species increases, and more culture clashes between humans and non-human animals develop.

While legislative frameworks must scramble to keep up, our understanding of animal behaviour continues to grow. But for dog guardians, and society in general, educational standards regarding canine behaviour and welfare requires improvement.

Dog behaviour is very very rarely unpredictable; dogs behave like dogs every time. It’s our perception of their behaviours that requires updating.

How can we be responsible?

Responsible ownership is a vague concept and commonly supported by statements such as keeping your dog under control (“effectual control” is specified in Irish legislation…) and to “socialise your dog regularly with other dogs” from this guidance. (“Socialise your dog” is another vague and inaccurate concept!)

The application of these concepts is vague and subjective. And to emphasise blame-messaging based on this weak foundation is irresponsible and not helpful.

Much like BSL, which firmly places the “fault” on dogs based on phenotypic characteristics, this messaging does little to affect change but sure makes it look like politicians are doing something, are taking a stand, despite evidence of effectiveness and enforcement being sorely lacking. (e.g., according to Karlin Lillington of the Irish Times)

In my discussions with guardians, impressions of responsible ownership often boils down to poop-scooping. Westgarth, et al, 2019, argues that “responsible dog ownership is a construction that emerges at the intersection of the needs of dogs, owners, and society.” Our relationships with dogs are contextual and variable, as are our views of our obligations to them and our responsibilities in ownership.

Before we can attempt to blame and legislate, we must educate and directing that requires an understanding of guardian-perception of responsible human behaviour.

Westgarth, et al, 2019, concludes “that what appears to be factual descriptions of responsible dog ownership practices that should be easy to follow are, in reality, a complex interplay of beliefs grounded in issues of ethical practice; perceived best interests of the dog; and the nature of

the social relationship with the dog. Responsible dog ownership means different things to different people at different times.”

How do we change minds? Well, we don’t.

Think back to the heights of the Pandemic and the controversies and discomfort generated toward daily and weekly updates from the science teams. While it’s normal in science for our approaches to change based on new and emerging evidence, this might seem like a fault in our work to outsiders.

Trying to change others’ minds with facts, data and information is not terribly effective. Considering information that doesn’t confirm our biases is rejected and rejigged by our protective cognitive systems which filter out these inconvenient truths, these ‘alternative’ facts’.

Challenging our own beliefs is uncomfortable and requires much awareness and practice. We can help ourselves and guardians understand that our previous position was based on what we knew then, and that we can update our thinking and our position based on what we understand now.

Instead of shaming and blaming, give ourselves, give them, an out.

Our beliefs are intertwined with our identity and particularly when it comes to those we care about, like our pets, of course we will take any challenge defensively.

How can we empathise with guardians to understand what they are really concerned about? What happens if they accept that their behaviour has led to their dog suffering or to their dog’s behaviour being unsafe? How can we help them acknowledge this, accept this, and activate solutions?

They are not wrong, no more than I am right. Right/wrong black/white is not an achievement. Another problem with us seeking out community online is that we are existing in that echo chamber.

Scrutinise that which satisfies your biases more closely. Challenge your own beliefs, no matter how strongly you believe.

Goal-Sharing

Looking at some interesting qualitative and ethnographic works on dog guardianship shows that multi-level interventions aimed at addressing a number of factors may be most effective. (Westgarth, et al, 2017)

For there to be progress regarding both examples here, we first acknowledge the care and love that guardians have for their dogs, rather than ‘othering’ and villainising them. Guardians want to understand their dogs’ needs but will need guidance and support in applying their developing understanding.

We all care about the outcomes for our dogs’ health and welfare.

Multi-factorial elements must be considered and applied. Shame and blame are unnecessary, ineffective and short-sighted.

While it’s believed, and heavily marketed, that having dogs is overwhelmingly beneficial for humans, the evidence is mixed at best. However, there are many challenges to caring for and loving dogs. (Owczarczak-Garstecka, et al, 2021)

Guardians require social support, practical guidance and empathy to maintain their dog’s welfare and for their relationship with their dogs to be mutually beneficial. (Merkouri, et al, 2022)

Let’s start there.

Great post. At this early in the morning long posts usually make me scroll on to read later ie never. You made some great points. The photos just reinforced the messages. The ‘be teachable. You’re not always right’ is a great one to try to achieve.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike