Decker at about 6 weeks and then at just under 6 months:

In what seems like only minutes, your butter-wouldn’t-melt puppy turns into a lanky, boisterous teenager.

Puppies are adorable and goofy, bringing joy and smiles to even the grumpiest faces. And while new puppy people often lament at the difficulties of puppy rearing, those are nothing compared to the drama that comes with canine adolescence.

Teenage dogs are the most at risk of becoming unwanted; Irish pounds and rescue organisations are filled with adolescent dogs needing homes and help. Adolescence is hard for adolescents and their humans.

Take it one or two sections at a time:

- What is canine adolescence?

- When is canine adolescence?

- Your dog’s brain on adolescence

- REFRAME!

- Guardians of adolescent dogs need support too

- The need for healthy relationships

- Adolescent dogs are vulnerable

- Preparing for adolescence starts with puppies

- Growing Pains

- Surviving Canine Adolescence

- What they don’t need…

- Dogs don’t grow out of behaviour ‘problems’, they just grow into them

What is canine adolescence?

Adolescence is a distinct developmental period during which puppies become adult dogs. Adolescent dogs experience much of the same adolescent-phase changes that teenage children experience.

When we think of typical teenage-antics, we might recognise:

- increased risk taking

- increased emotional sensitivity

- increased social motivation

- decreased behavioural inhibition

- increased conflicts with care-givers

We’ve all been there…

Adolescence is a time of change

- physical, endocrinological, neurological

- behavioural

- sexual & reproductive behaviours

- social roles & behaviour

The guardians of teenage dogs also experience changes in response to their dogs’ development.

Behaviours once considered naughty or entertaining in puppies are now considered deliberate & defiant. Their puppy has shed much of their “cute” infantile features and now humans have much higher expectations of their adolescent.

(Owczarczak-Garstecka, et al, 2023)

Teenage dogs are a work in progress with a brain under construction. They are not ready for adulthood or adult expectations.

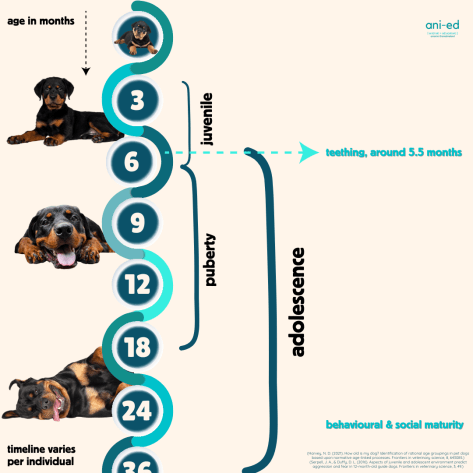

When is canine adolescence?

Although there will be individual differences, adolescence begins around the time they get their adult teeth and begins to level off as they approach social and behavioural maturity between 2.5 and 3 years.

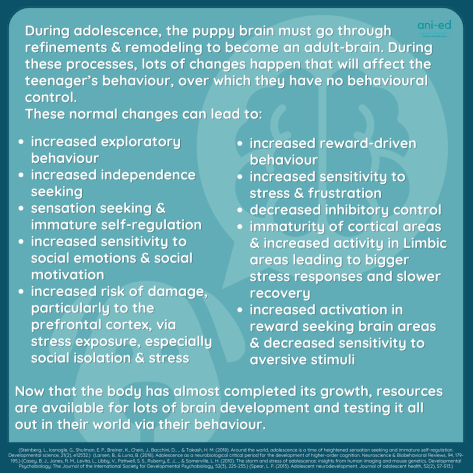

Your dog’s brain on adolescence

Teenagers have to progress from baby helplessness toward adult independence and to do that their brains and bodies need to go through a lot of change.

They have to become more independent, be able to make decisions and think about which information to apply to different situations – adults have to do things that are basically the opposite to puppies!

With body growth almost done, there are resources freed up for brain development and for behaviour to test it all out in their world.

(Casey et al, 2010) (Larsen & Luna 2018) (Spear 2013) (Steinberg, et al, 2017)

During this stage the brain is gradually becoming a better thinking, decision-making organ but while this is happening it doesn’t function very well as a thinking, decision-making organ at all.

Parts of the brain that look after learning, concentration and impulsivity are busily being built rather than helping the teenager with coping with stress and recovery. And just like when a motorway is being remodeled there are diversions; information and messages in the teenage brain are diverted, to more reactionary areas, while the brain is getting its make over. This often results in over-the-top reactions and slow recoveries (we’ve all been through it so this should be no surprise).

Along with brain re-modelling, the teenager’s body is bathed in changes and swings in hormonal shifts preparing their bodies for social contest, reproduction and parenthood.

All the while, the teenager is getting their adult teeth and their adult bodies, grappling with these changes and learning how to put their new body to good use.

With their bigger, bolder and stronger bodies, changing brains and responding, adolescent behaviour may come as a surprise. But really, quite a lot of it is due to them clearer, better at communicating more obviously, and being bigger and stronger.

What happens to a dog in their first year of life is most impactful on their adult behaviour and behavioural health (Foyer et al, 2014). While we now give lots of attention to puppy-training, once puppies hit adolescence, we often wash our hands of those puppy-protocols and send the teenager off to obedience-and-manners land.

Adolescent dogs need careful guidance and their developing behaviour requires nurturing. Adolescence is a time of change & challenge for teenagers and their carers.

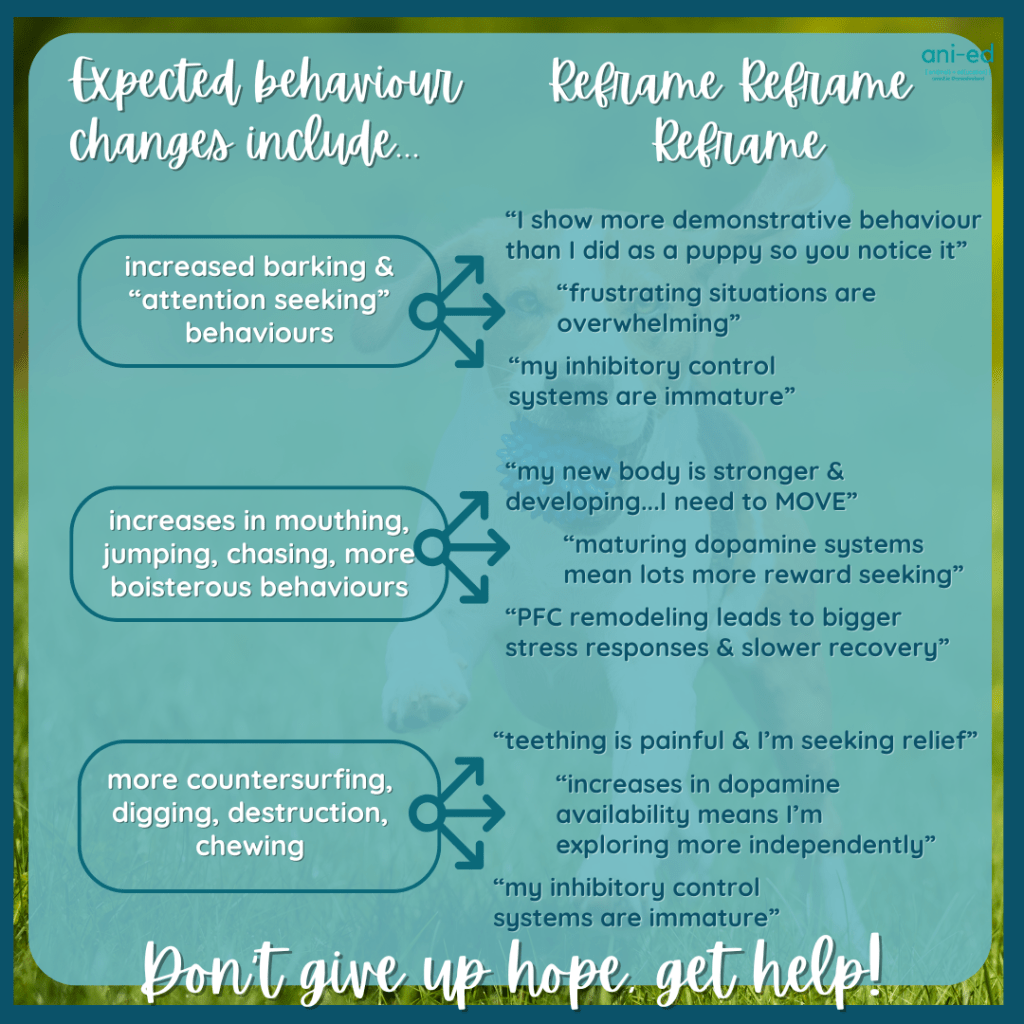

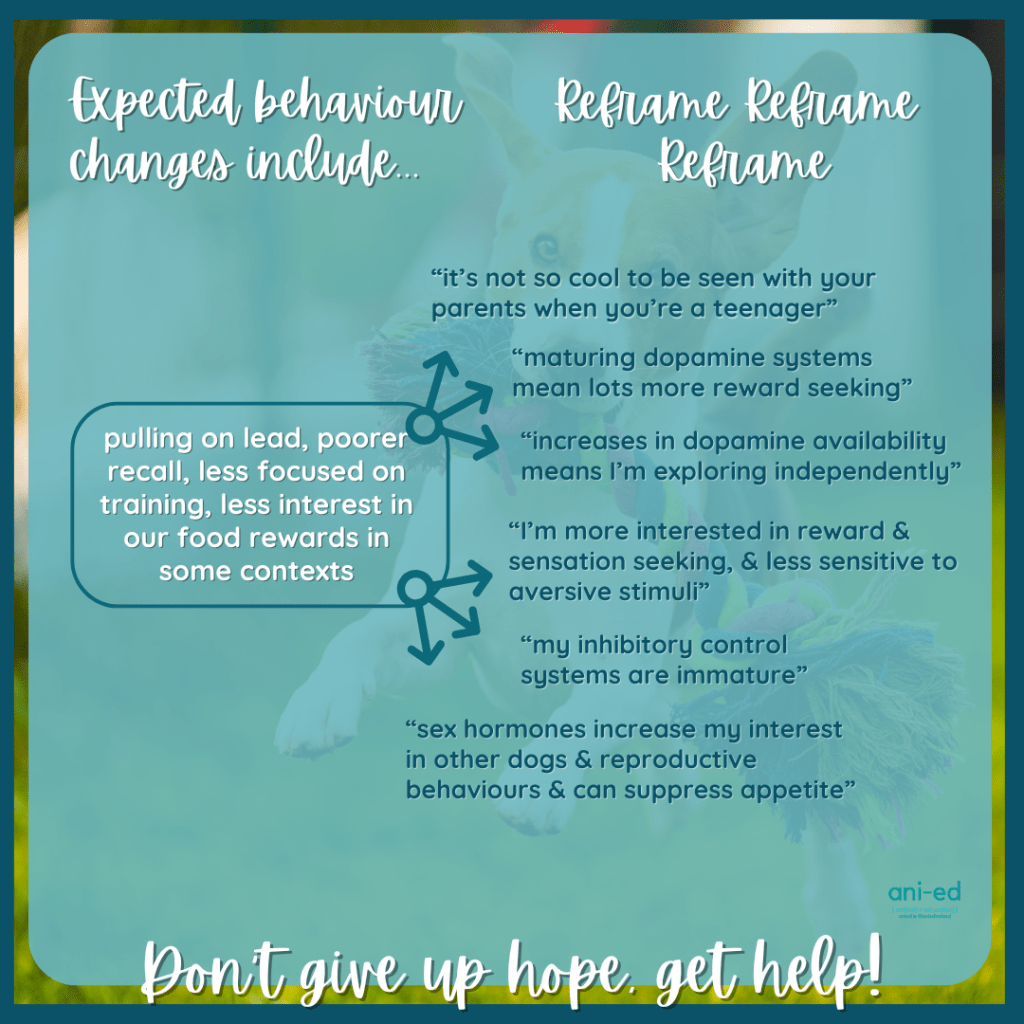

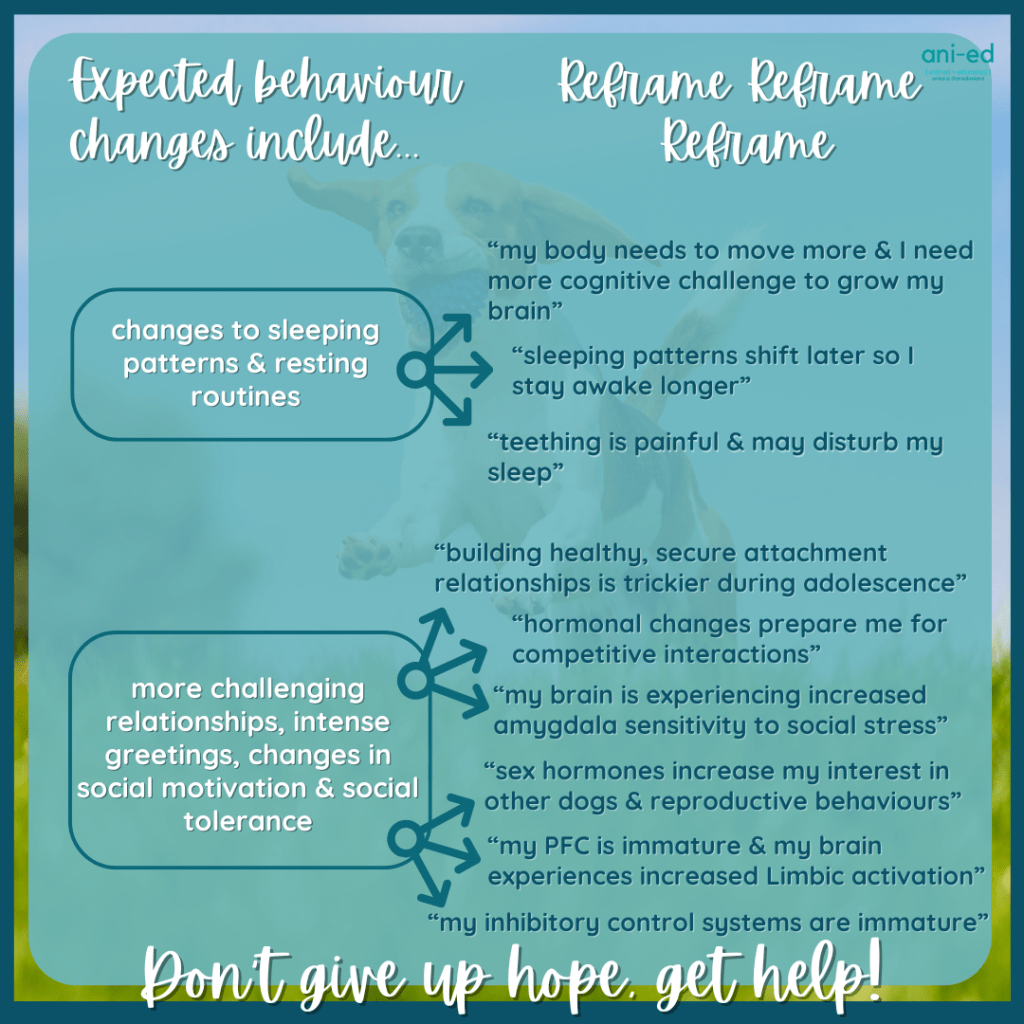

REFRAME!

Understanding your teenager helps you reframe their behaviour and appreciate what they can, and can’t do!

It may or may not be of great comfort to hear that your adolescent dog’s behaviour is outside their control, and likely a normal part of their being a teenager. But there is hope and there are plenty of things we can do to help our dogs. And for the rest, we just need to survive it!

Adolescent dogs need understanding, more support, more patience and some time. Same for their guardians!

Teenagers need our help…they just have a goofy way of asking for it sometimes! Your dog’s behaviour is information & we just need to learn the best ways to respond.

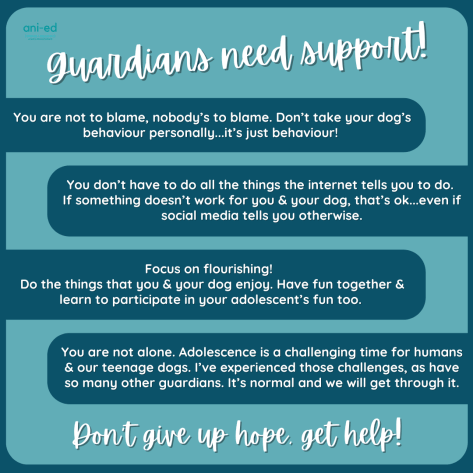

Don’t give up hope, get help!

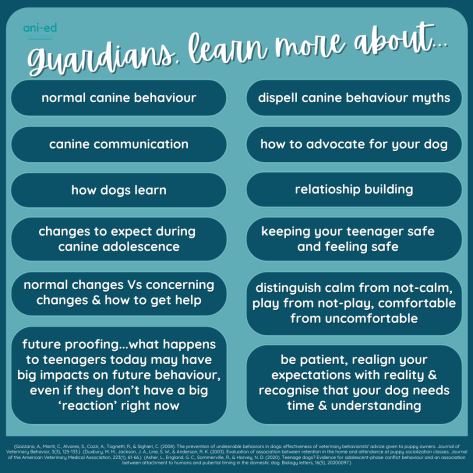

Guardians of adolescent dogs need support too

It can feel very lonely to live with a teenager, and guardians might feel blamed for their dog’s behaviour. Preparing guardians for what they can expect as their dog develops from puppy to adolescent can help with improving outcomes for both ends of the lead.

(Duxbury et al 2003) (Gazzano et al, 2008)

As puppies grow into their new bodies, they lose a lot of that typical puppy cuteness. This changes their guardians’ attitudes toward them and along with the passing of time, guardians will expect their lanky teenagers to behave more like adult dogs.

Human perceived ‘cuteness’ is important in predicting the quality of human-canine relationships.

(Owczarczak-Garstecka, et al, 2023) (Thorn et al, 2015)

Guardian perceptions of their dogs’ behaviour change as their dog ages, with very different expectations of puppies versus teenage dogs.

Remember, adolescent dogs are a work in progress with a brain under construction.

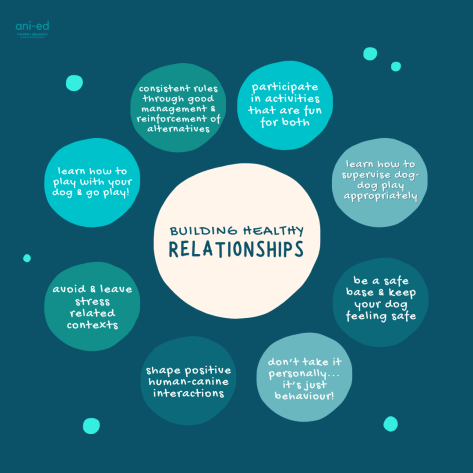

The need for healthy relationships

It is well recognised that relationships between teenagers & their care-givers can be strained. (We’ve all been there!) There appears to be analogous effects affecting human-canine teenager relationships too.

While we should recognise that our relationships with our adolescent dogs will be strained for some time, we can also focus on relationship building to develop healthy, secure attachment relationships. The payoff comes a few months down the line but this is a priceless investment.

Adolescent education emphasises protecting our teenagers from unhealthy stress & building healthy relationships.

Guardians of adolescent dogs are often blamed & feel judged for their dogs’ behaviour. There is no place for blaming & shaming.

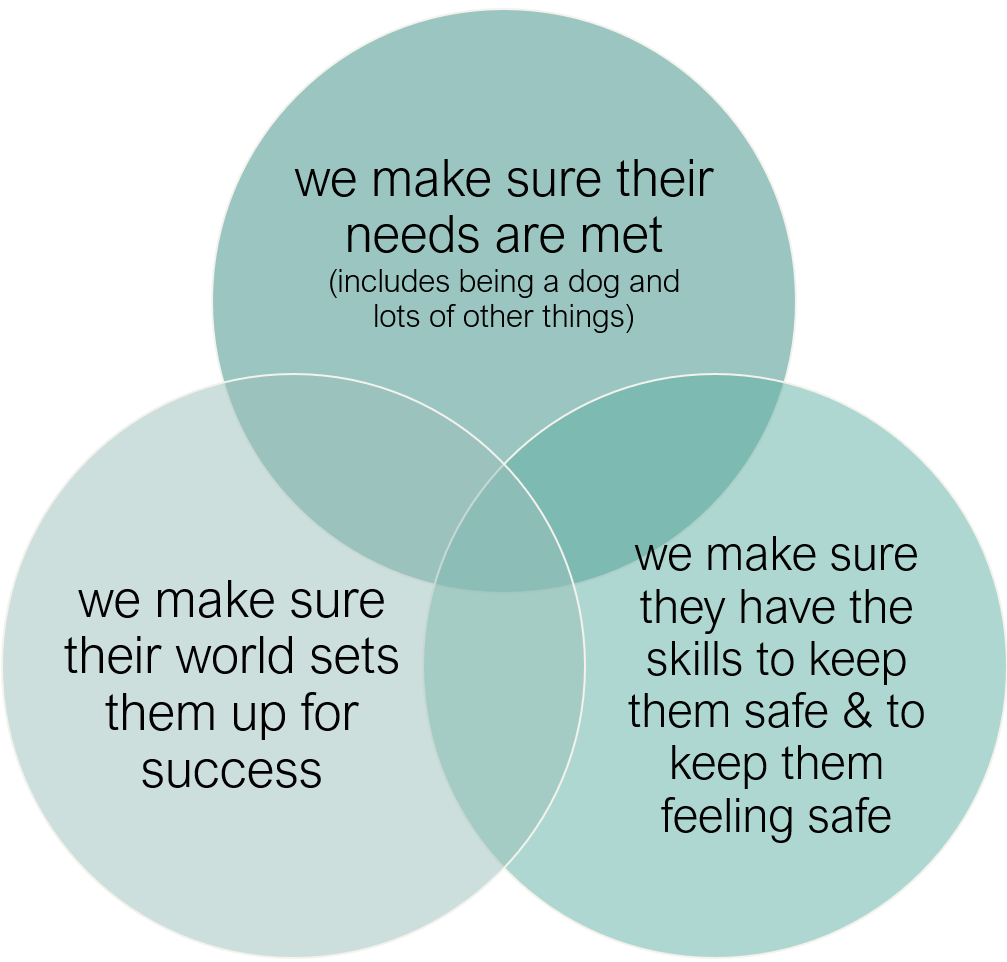

Be empowered by the understanding that you can make appropriate adjustments to your teenager’s environmental conditions, supporting healthier behaviour and & behavioural development.

Find the right professional to help you & provide you with appropriate evidence-based explanations for your dog’s behaviour.

Teenage dogs are vulnerable, and so are their guardians. Get help to keep your dog safe & with you.

Adolescent dogs are vulnerable

Adolescent dogs can’t win. Their adolescent behaviour, over which they have no control, gets them killed because they live in an incompatible human world.

Teenage dogs are a work in progress. They are trying to navigate the complex & (relatively) under-enriched human world with a brain under-construction and in a social environment holding unrealistic expectations against them.

We, as humans with all the control, can learn to support teenage dogs, setting them up for success & ensuring a safe place for them in our human world. But we have to do the work.

Your adolescent dog is not trying to give you a hard time, they’re having a hard time!

Not only is adolescence wreaking havoc with their brains & bodies, but their behaviour puts them at increased risk too.

- adolescent dogs are most at risk of becoming unwanted & relinquishment

- dogs under the age of three are more likely to die due to behavioural euthanasia

Given their brain is under construction & particularly sensitive to stress, further exposure to stress may be more impactful, potentially contributing to the development of trauma/ trauma-like responses.

(Corridan et al, 2024) (Pegram et al, 2021) (Powell et al 2021) (Salman et al, 2000) (Talamonti et al, 2018) (Weiss et al, 2014)

Preparing for adolescence starts with puppies

We can begin to help our dogs prepare for adolescence when they are still puppies, just by having a little awareness of what’s about to happen in the coming months. And we can help puppy people prepare before their dog hits adolescence too!

Puppies appear more tolerant than they often are. Their communication and behavioural systems are not mature and we can find it trickier to interpret their responses. That can lead us to put puppies in some unsuitable situations…we do lots of stuff to puppies that we just don’t do to adult dogs as they wouldn’t be appear so tolerant.

You can imagine the associations puppies are making during this impressionable time. As they move into and through adolescence, they become better at saying NO! or WAIT!, or more so, we become better at recognising their objections. We think they have become more difficult, but they may just have had enough, and now they can let us know more obviously.

Of course, not everybody gets to meet their dog as a puppy, and sometimes, we are jumping right in during adolescence.

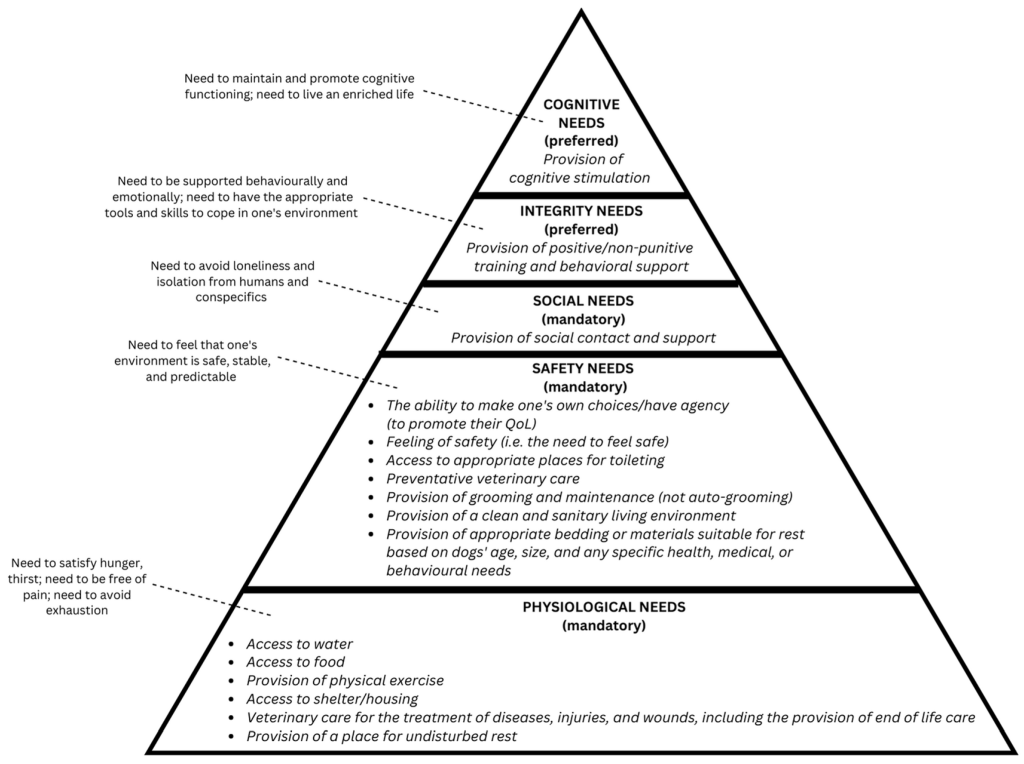

While we might have a little idea of what’s going on inside their brains and bodies, it’s their behaviour that is information for us. We can apply that information to ensuring we are meeting the needs of the individual teenager today, & into the future.

There is a tendency to dust off our hands and draw a line under puppy training, moving onto adolescent education as if it were a different entity altogether. Teenagers require just as much specialised support as puppies and their humans even more so.

Adolescent programs should be a natural continuation of enrichment-based puppy programs, which are dog-led. Certainly, that’s the way we do it!

Growing Pains

The perfect puppyhood honeymoon is over…adolescence has hit and teenage behaviours are rearing their ugly heads.

Adolescence brings an increase in activity, strength, fitness, vocalisation, swings in responses, destruction, spookiness, aggressive responding, distress, humping, distraction, toileting & marking, difficulty with calming and interest in the opposite sex.

Sounds like fun, right?

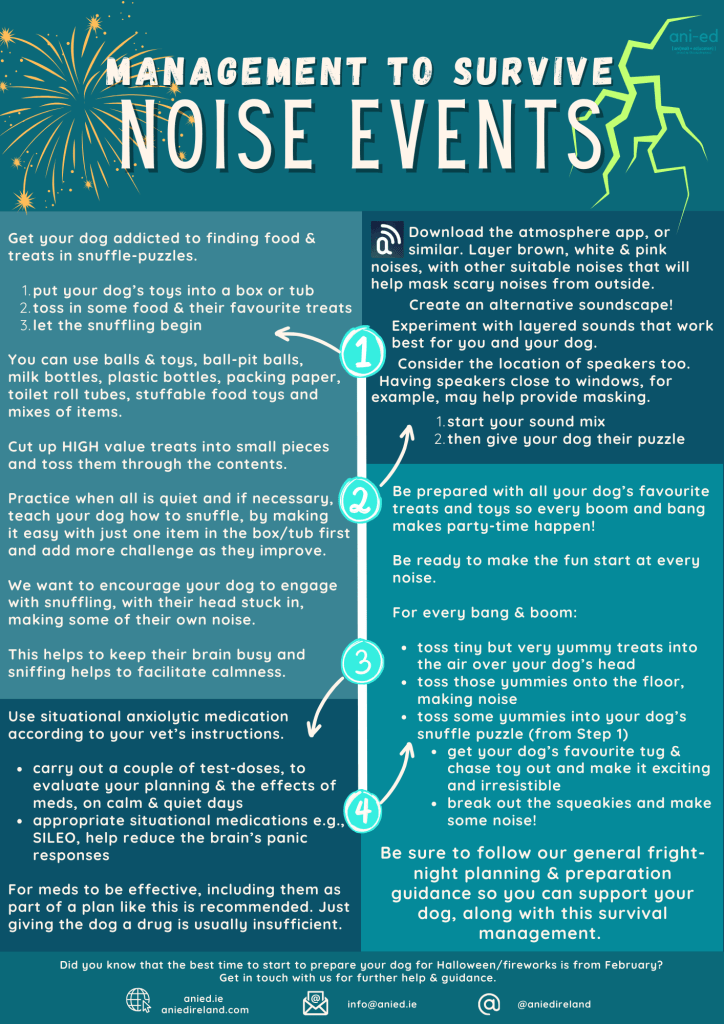

Surviving Canine Adolescence

Having a good start with puppy training and appropriate social and environmental exposure certainly helps, but for the most part, adolescence brings challenge.

Manage to prevent adolescent behaviours sticking: although teenage behaviours relate to transient changes, they can stick particularly when accompanied by a rich reinforcement history.

Management means we set our adolescent up for success by preventing them being put in situations where they may carry out unwanted behaviours. Pros, this requires skilled antecedent arrangement.

Continue with appropriate social and environmental exposure: teenagers are probably more likely to appear to over-react when experiencing emotional swings, which are just more dramatic during adolescence.

Make sure teenagers get lots of space from stress-cues, have options for how they engage in social interactions, and continue to pair good things with exposure to social and environmental stimuli.

Supervision and observation: although most associated with puppy training, supervising of the teenager is useful too to stop destruction, humping and leg lifting before it happens, by redirecting the teenager to other more appropriate outlets.

Close supervision of dog-dog interactions is especially important, particularly where a number of teenagers hang out together.

Teach them to be good human trainers: teenagers tend to have trouble with waiting their turn, calming themselves after getting wound up and engaging with their people in the midst of distractions.

Teach teenagers how to train humans to get the things they want to help them to choose their human over the goings-on. This is more about you becoming easy to train!

Physical and Mental Exercise: teenagers are stronger and more active than puppies, all of a sudden. They will need increased physical and mental exercise, while carefully helping them avoid frustration and recover from getting wound up.

Improve the value of rewards: puppies bask in their owner’s love but it’s not so cool to be seen with your parents when you’re a teenager.

Building motivation for interaction with you, choosing you, and for play and fun with their person certainly goes a long way to boosting engagement.

Remember, rewards are things the dog chooses – what is the dog already doing? That can often give you information about the things that your dog likes to do. Making sure they get to do these activities is important, just as participating with them, keeping it fun and helping them choose engagement.

Clarity and Consistency: more than at any life stage teenagers need to be able to predict what’s going to happen to them. This is largely about you being consistent and clear in all interactions with them.

While management to prevent unwanted behaviour is important, rewarding desirable behaviour is essential too.

Take responsibility for your dog’s behaviour and set them up for success .

Accepting responsibility: the ‘Teenager’ label is used to get guardians out of all sorts of trouble but the human end of the leash must take on the challenges of living with and supporting an adolescent.

Humans tend to hold the teenager more accountable for their behaviour; they are not so cute anymore and “should know better”.

The popular opinion that teenagers are stubborn and belligerent is flawed; teenagers can’t know or do better; some days their brains are not going to be working quite right and on most days, teenagers, as opposed to puppies, will not put up with mixed signals from their teachers.

What they don’t need…

More wild & crazy is probably not helpful

The temptation is to try to tire the teenager, to run them, to have them engage in high-octane activities like group dog-dog play or repetitive fetch games.

Dog parks, daycares and play groups may not be the best place for adolescent dogs to develop appropriate social skills, and may cause teenagers to associate high arousal with other dogs and the related excitement. (HINT: they probably already associate being wound up in these contexts…)

Regular repetitive exerting activities are also likely to lead to increasing arousal, difficulty with calming and becoming harder to live with.

Appropriate social and environmental exposure, along with suitable mental and physical exercise, are the keys to helping you and your dog through adolescence. Get help, get committed and remember that your teenage dog is not trying to give you a hard time, they are having a hard time.

“Frustration tolerance” and “impulse control” training may be misplaced

The teenage brain is poorly equipped to tolerate frustration or exert “impulse” control. Why then, do so many training programs emphasise such poorly defined fuzzy concepts?

Our dogs’ behaviour tells us what they are ready for and what they are not quite able for just yet. Program design should set learners up for success by listening to what their behaviour is telling us.

Adolescent development tells us that they need appropriate cognitive challenge, without frustration, opportunities to move, lots of exploration & building independence. And we must learn to keep them safe & manage their world carefully.

Dogs don’t grow out of behaviour ‘problems’, they just grow into them

Teenage behaviours don’t stop just because your dog matures and ages. If anything, these sometimes worrisome behaviours just become more established and honed, and more serious and adult-like.

Behaviour happens in the environment, even when related to brain or hormonal changes, so the adolescent’s environment requires adjustment and ongoing, responsive adjustment throughout development.

We can make the right changes to support adolescent dogs, with the right education and understanding!

Remember, your adolescent dog is having a hard time rather than trying to give you a hard time. But this is your time to step up, keep supporting your teenager, and helping them develop coping skills for adult life.