Just over 1100 words and about 6-ish minutes read time for this one.

9th December marks the International Day of Veterinary Medicine, recognising the vital contributions that vets, and support staff including RVNs (a valuable profession in and of its own rite), make to animal health & welfare, public health, food safety, policy development and their roles in One Health One Welfare applications.

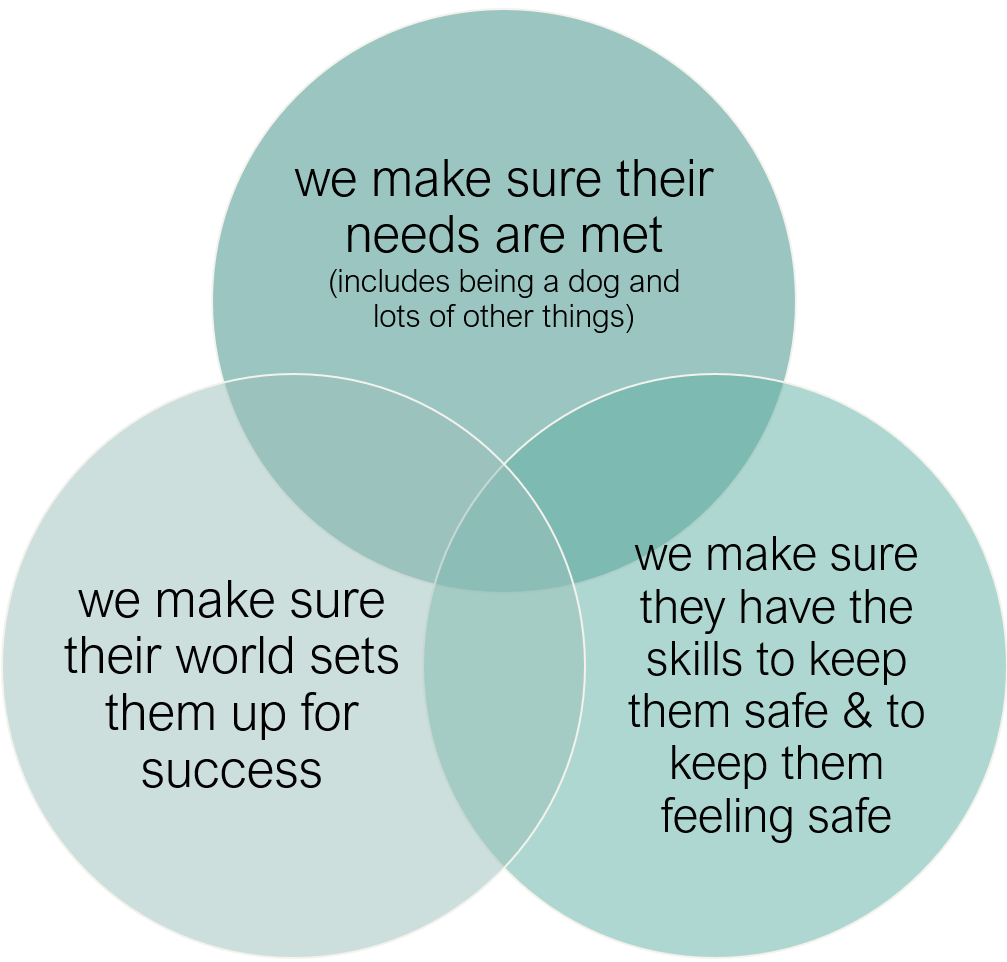

My favourite cases are those where we get to collaborate and create a care-team for the dog, working alongside allied professionals including the dog’s vet-team. I am so lucky to get to work with some wonderful vets, alongside my clients, creating dream-teams to help pets and their people.

On social media, I regularly, and most recently, see references to “pain trials” and how ‘pet owners’ will need to accept that this isn’t a quick-fix scenario. While I agree that trial analgesia can be lengthy, costly and even overwhelming, it’s up to behaviour professionals to ensure that we are communicating with both our clients and vets, supervising the behavioural aspects appropriately, and collecting and presenting data suitable to both clients and vets to ensure progress can be made.

The buck stops with us.

If the end user/s, clients and vets, are having difficulty with our interventions, rather than targeting external accountability, start within. What can we do better?

A boy who cries pain

It certainly is easier now, more than ever before in my career, to discuss the relationships between physical health, disorder and behaviour. High rates of occurrence of physical contributions are often cited as relating to behaviours of concern, across research, e.g., Mills et al, 2020, and anecdotally from professionals (e.g., in 2024 ~60% of AniEd cases included physical contributors).

While improved recognition is good, there are still gaps in our knowledge, and in the procedures we apply to communicate the relationships between pain and behaviour.

It’s not enough for behaviour professionals to declare that an animal is “in pain”, or lament that the vet just needs to prescribe and get on board. Pain is a multi-dimensional, subjective experience (Wiech et al, 2008). that we can’t rule out on behalf of another individual. It is not easily detectable during visits to the veterinary clinic and diagnostics, like x-rays, can’t provide definitive answers either.

But, fear not! Behaviour is our super-power (in more ways than one!). Behaviour can and should be considered part of clinical signs to inform diagnoses and treatments (Dinwoodie et al, 2021). And we can act as translators between clients & their dogs and the vet-team.

We must be specific and clear. We cannot expect guardians and carers to observe and interpret their dogs’ behaviour – they often do not have the skills for such specific observations, and, it’s incredibly difficult to be objective about your own loved ones.

We must collect information via questionnaire and interview techniques, we must make direct and indirect observations of the dog’s behaviours, and we must support our clients in collecting ongoing data (there will be spreadsheets!). We take this from our clients and translate that into appropriate terms for the dog’s vet-team. No vague statements or euphemisms – actual observable behaviours and evidence-based language that can relate to diagnostic and treatment approaches.

Only the vet can decide on medications, treatment options and diagnostics. But that doesn’t exclude or devalue our contributions, it’s a collaboration!

Behaviour is still in the environment

With our increased awareness and willingness to discuss the bidirectional relationships between physical and behavioural health, it’s everywhere. But as with anything that may be treated as social media fodder, extremes and polarisation are rampant. Pathologising behaviour is widespread as we become convinced by current trends and blinded to the nuances of behaviour.

Of course this infects our insistence about client or veterinary attitudes to our efforts – they are mistaken, their expectations are unreasonable, them, them, them…

Trial analgesia isn’t some panacea. Behaviour is still in the environment. The painful dog’s distance increasing response, e.g., growling and snapping, is still negatively reinforced when the hand reaching for them withdraws. And that response can be maintained beyond our analgesia efforts.

Trial analgesia is just one piece of the puzzle

There are many different types of pain and many types of pain relief. History, data collection and observations may provide some insight into the types of pain potentially contributing to behaviour. Also, it might not.

We can’t just throw things at the wall, hoping something sticks. We form hypotheses using observable behavioural data and our efforts must be falsifiable. Collecting the right data allows us to determine if trial analgesia is appropriate, and, when and what adjustments may be trialed next.

Expectations must be realigned with reality and a roadmap produced for both client and vet-team so we are all on the same journey together. Both need to understand observations that indicate we’re on the right track, and when we’re not…and what that might mean for our plan.

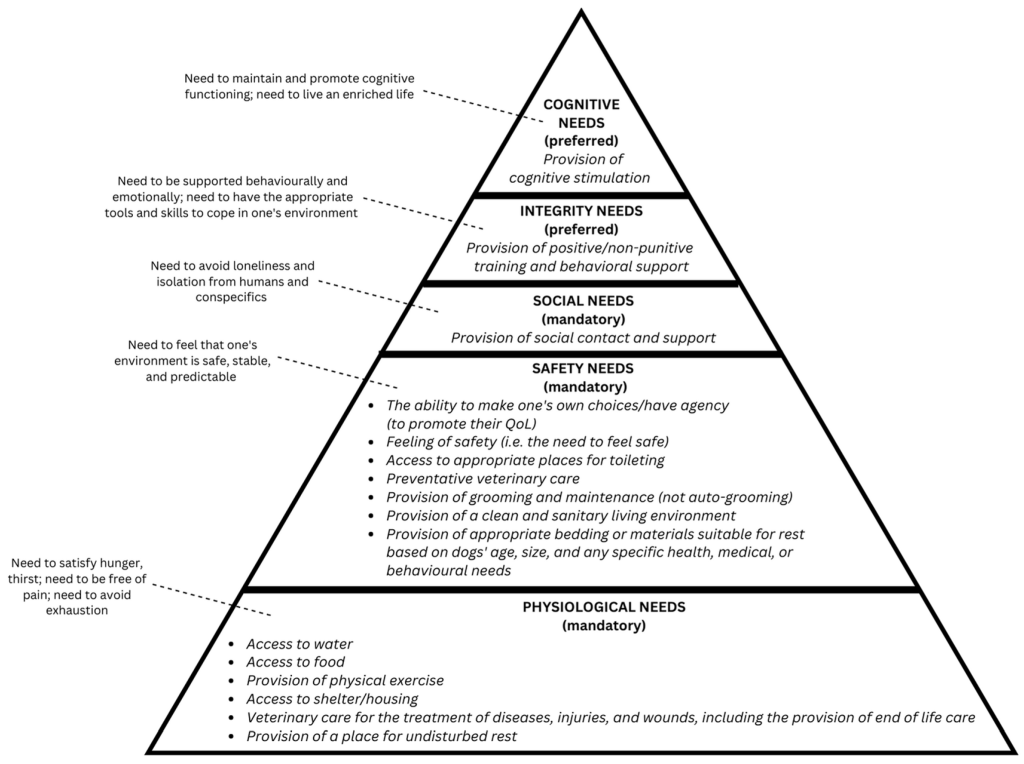

In this collaboration, we are constructing just a fraction of the plan: the clients contributes their bit, the vet-team their bits and the dog must have a say too!

Trial analgesia should be at least 4 weeks, but for clearer data collection, up to 8-12 weeks can be better (Mills et al, 2020). We are not expecting some magical turnaround…remember, behaviour is still in the environment. And we might continue to trial and collect data, or, we might pivot and look at alternative analgesia with continued data collection. We are supervising and supporting along the way (so many shared spreadsheets!).

Given that chronic pain is a chronic stressor, it makes sense that anxiolytic medications may also be indicated (Mills et al, 2020) and may support increased plasticity, helping the brain heal, recover and adapt (Jetsonen, et al, 2025).

Starting both at the same time is sometimes required to improve welfare, but can muddy the waters in our data collection. However, effects can be distinguished at a later time when we have progressed through our intervention plan a little.

Pain relief is not just about pain relief! Pain is multi-systemic affecting behaviour, cognition, inflammation, activity and social interactions. And that means multi-modal pain relief as part of our intervention programs.

Nuance

At AniEd, our professionals and learners do courses and CPD on behaviour health as health, communicating and collaborating with veterinary and allied professionals, and on supervising, guiding and supporting clients in data collection. This is no time for superficial or tenuous recommendations.

I’m not suggesting that awareness of a need for treatment of pain, and other physical contributors to behaviour, should be downplayed. Nope, we have fought hard to build this recognition and we continue to do so.

There must be balance and consideration for how we communicate, supervise and support these investigations as collaborations, as part of team building…building that dream-team.