When faced with a loved one’s mortality, perhaps they are getting on in years or perhaps there’s been a particularly damming diagnosis, it’s pretty natural to think of all the things we might want to pack into the limited time we have left together.

Bucket lists for dogs have become a social media staple. Videos and photos of guardians, and their truly loved dogs, sharing their last moments together, bring me to tears.

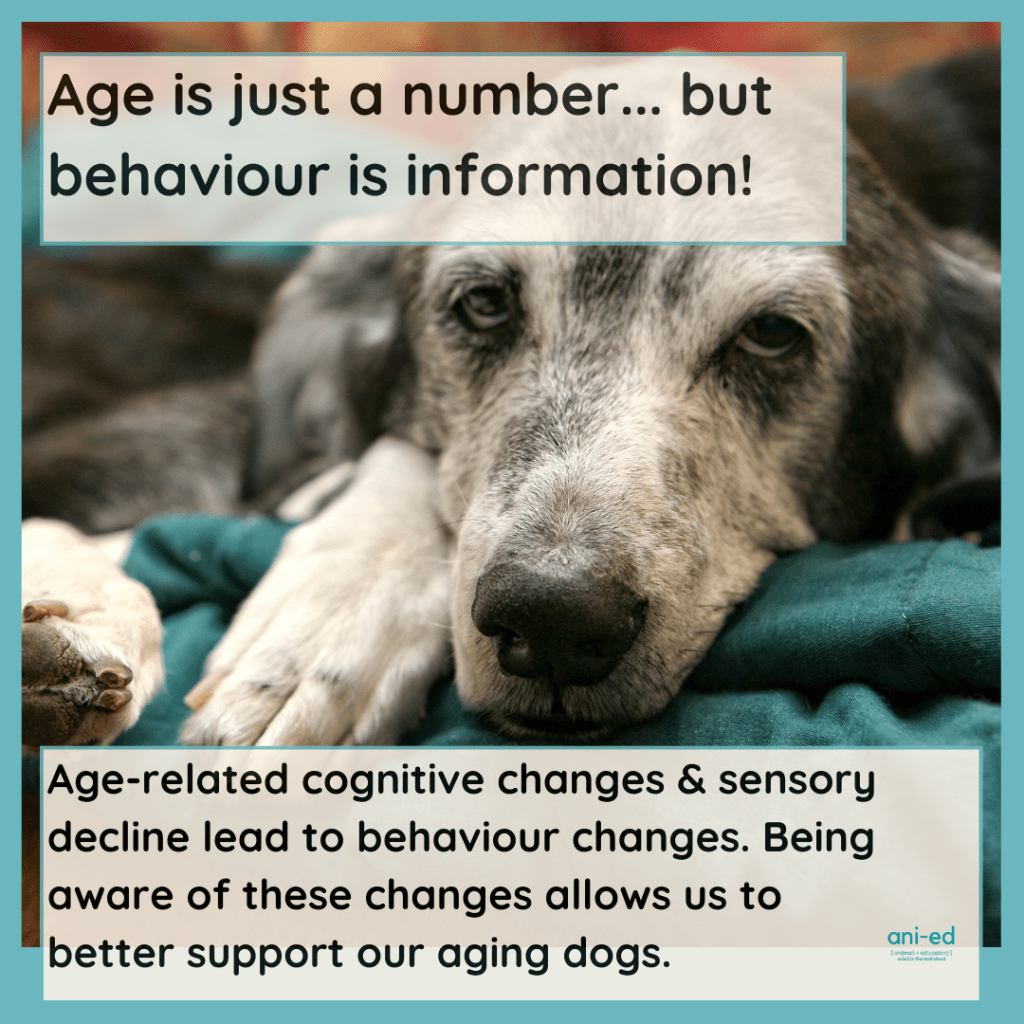

Finding ways to cope with our dogs’ aging is certainly something that’s important for the support of senior-dogs’ humans. The changes relating to canine aging can put significant pressures on our relationships, as well as pressures on resources and finances.

Care-giver burden is very real for those caring for senior dogs, particularly where chronic conditions are confounding aging (Spitznagel et al, 2019). This care we devote to our aging dogs intensifies our attachment (Martens et al, 2016) and can blind us in making the best decisions for our dogs (Christiansen et al, 2016).

Who are bucket lists for?

When faced with a more imminent ticking clock, our minds naturally drift to all the things we didn’t get to do with our dogs, throughout their lives or perhaps during their more spritely years. Regret is normal and very much a part of anticipatory grief.

Constructing a bucket list seems to provide a solution. We can focus on maximising our time together, no matter how short, and I can see how posting about it might be an important part of processing this journey, of generating a support structure, and of basking in the loveliness of our experiences together.

It’s probably easy enough to devise a list of all the things you might not have had the chance to do together and things that you would like to do now that the chips are down. But are those the right considerations?

I’ve two other questions that I want you to ask…

- What does my dog LOVE?

Does your dog really want to go kayaking or to totally new or overwhelming places? Your older dog, whose health, condition and mentation might not be what it used to be…

All these weird and wonderful places and activities certainly sound amazing, but most dogs, particularly older dogs, just might not enjoy the changes, the new challenges and the pressures.

For sure, novelty and excitement make for great memories, but what might our dogs prefer to do? Your dog wants you, they want to know where you are, have you close to them, for you to be predictable and make all the good things happen.

2. Why wait?

I took Decker’s nose print and paw prints years ago when some offer on a kit came up. When I shared the prints, there was much panic about whether we might be preparing for the end.

So why do we wait until it’s almost too late, until our hands are forced by time, to do all the last minute things?

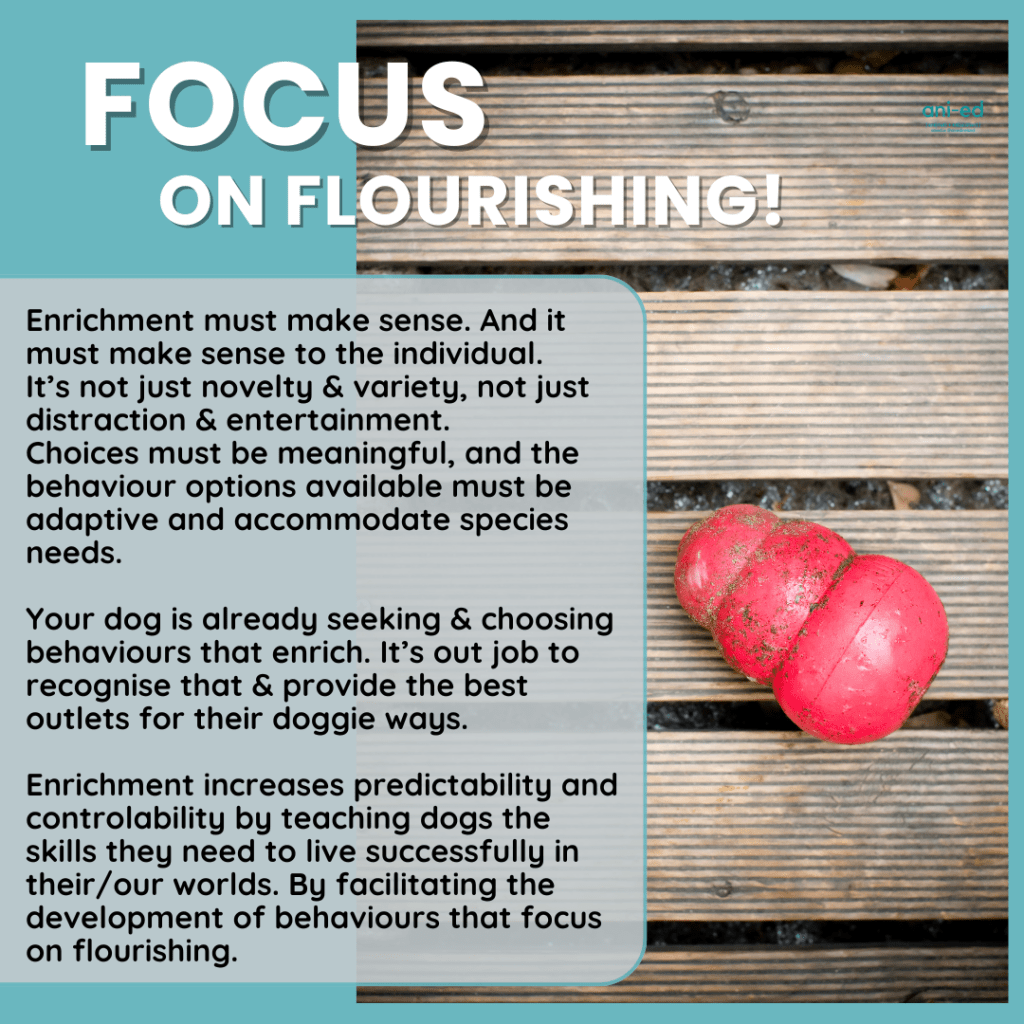

Dogs live life as if it’s a bucket list

Dogs are just about the best living representation of “live every moment to the fullest”, or some other similar motivational poster.

They appear to be lucky enough not to have the cognitive powers to worry about their mortality, to lay awake reflecting on what might have been.

But regardless, dogs are in it for NOW and TODAY. They are not considering what life might be like in two years time; dogs are their current life and experiences. As I always say, dogs are here for a good time, not for a long time.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot more lately because Decker has just recently got an all clear after a cancer scare.

F**K CANCER

Since the beginning of this year, Decker’s aging has become more pronounced. He’s 12.5 and that’s pretty ancient for an AmStaff.

During a routine exam, his vet incidentally found a concerning growth in his rectum. Growths of this type in this area in old dogs usually indicate adenosarcoma and all the unpleasantness that brings. With the prospect of maybe 3-6 months left, my anticipatory grief accelerated and my efforts to consciously make sure we didn’t dwell for a second intensified.

After three months of monitoring, biopsies, and finally, surgery, the lump is out and to everyone’s great relief it’s a leiomyoma. A benign growth that’s generally done after surgery. Phew!

But this has been weirdly conflicting. His tentative cancer diagnosis gave me some feelings of control over the timelines and predictability for what I might expect; how the end might look and when it might happen. I’m glad it’s not cancer but I’m left a little bereft.

Aging ain’t all it’s cracked up to be.

We are told to cherish and enjoy our aging dogs, their greying faces and slowing bodies. But I don’t find any of this magical and I’m not particularly enchanted by it.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m grateful for every second more we have together. In my mind, our time together has always been limited as he has lived his life at top speed with little concern for the ramifications.

I miss our super-charged, gung-ho lives together, as much eye-rolling and worry as that’s inspired. It’s still full on, just relatively less so. I feel we don’t and wont have enough time to bask in this slower pace. And I’m really grieving for something, not sure what, now that’s he pretty deaf.

From about March, his failing hearing appeared to deteriorate even more and although he can hear some sounds, that’s sure to go soon too. This has been the greatest smack in my face that we are heading toward the end.

I feel almost handicapped in communication and my views toward our relationship have changed. We have worked for years and years to have so many behaviours on verbal cues, under pretty solid stimulus control. He has had so much freedom throughout his life because we worked so hard and built a pretty rock solid reliable recall.

And just like that, it’s gone. It’s redefining every aspect of our lives together and I’m not sure I’m ok.

Let me just say that he has not been affected in any way and I’m working really hard to make sure there’s no outward signs of my internal turmoil.

A small celebration. Just a couple of weeks we figured out that he can hear this Acme whistle. He clearly doesn’t recognise the conditioned sound previously learned over years, but he hears something. And that means I was able to condition it as a new recall cue. After three weeks of practice, and building a solid whistle recall (again), he was able to recall off water…which is pretty much our biggest challenge.

Every day is his bucket list

Decker has always been the best reminder that life is short, not because he’s now an old fart, but because, since the day he landed, he has put 110% into every action. If any of his days were to be his last, he would have zero regrets and he would have soaked up the joy from every single second.

We don’t need some end-of-life bucket list. He is living his fullest and best life every single day. He throws himself, full-force, into every thing even the mundane. He seeks and finds the fun in everything and thankfully, his attitude is somewhat contagious.

I can’t possibly live in the wallowing or introspection while he is by my side doing it all. Not reflecting or thinking about it; doing it, living it, feeling it, experiencing it. Every second.

So we are not doing a bucket list, we are doing what we’ve always done. Going to the beach for swimming, walking in the woods, sniffing all the sniffs, playing ball games and tug, having fun with food, chewing and destroying all sorts of things, hanging out and sharing space, sleeping deeply beside one another.

I might seem like just the facilitator, making sure he has all the resources to continue to enjoy all these activities for as long as possible; but I’m also a witness to it, basking in his continuing joy, and if I’m lucky, I’m also a sponge, soaking up his attitude, benefitting from his joie de vivre and hoping that just a little bit rubs off on me.

Interested in learning more about canine aging and supporting our senior dogs? We have a webinar for that! More here.